A Mathematical Philosopher

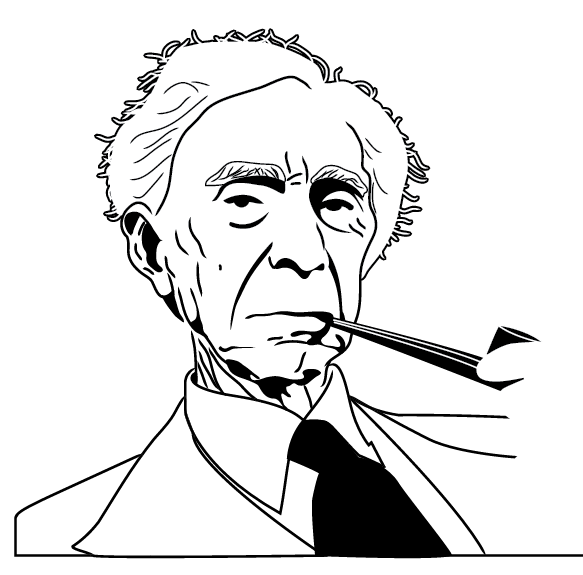

I want to start by quoting Bertrand Russell. For those who don’t know, Bertrand Russell is dead. He used to be a mathematician — but that was many years ago — and the reason I bring him up is, in some ways, irrelevant to this fact. He is important not because I knew him personally and he affected me specifically in some way, but rather because in his writings he seems to attempt making intertwined the various ideologies of human thought (that I try to acquaint myself with) which he concerns himself with. A title of one of his essays, for example, is Mysticism and Logic, which are two ideas in human thoughts ordinarily unrelated. In the essay he attempts to bring together the two theories of Mysticism and Logic. I believe this to be a general human faculty, combination or unionization, some kind of method bringing together previous ideas in important, new, useful ways.

un·ion /ˈyo͞onyən/ noun

the set that comprises all the elements (and no others) contained in any of two or more given sets.

In examining this sort of unionization of ideas, one probably asks about the reasonable platforms which the ideas might be constructed upon. Perhaps one could argue that it is through the English language that one constructs ideas. This would seem reasonable by the way that I am communicating ideas in the moment now. I make references to things, then use the points made by the things referenced to not only inform about the old theories referred to by the references, but pursue making of them something meaningful and relevant to the present (or at least meaningful and relevant to me).

How I see it, Bertrand Russell presents everything by a kind of logical proof. He asserts relations between objects in ordinary existence. He determines the truth or falsehood of the statements in relations to themselves. Then attempts determination of all of the possible outcomes given the assumptions. These assertions, however, require something to make it all plausible. He often times makes his arguments through ordinary English, but he could also present the ideas in other languages that he is well aware of — like French and German, which are two other languages belonging to him — however it was at the beginning that I called him mathematician, and so it is rather with the particular platform of mathematics that I believe he authors the native beliefs of his sentence constructions.

It is my belief that mathematics represents that without ambiguity. I have come to find that more natural languages cannot represent exactly what mathematics does, even though these languages are eventually the things which share the details of the mathematics. In Mysticism and Logic Bertrand Russell claims there is a “mystic insight” which “begins with a sense of mystery unveiled.” I believe this to be a sort of abstract mathematics that makes up everything humans wish to share in detail. He continues to say:

“The first and most direct outcome of the moment of illumination [mystic insight] is belief in the possibility of a way of knowledge which may be called revelation or insight or intuition, as contrasted with sense, reason, and analysis, which are regarded as blind guides leading to the morass of illusion.”

People regard science as that which is correct. However, science can only provide evidence to that which does not seem wrong. An assertion of the abstract cannot be refuted as it is not bound in concrete existence whereas science deals with that which is concrete. In this way, it is intuition which is proper where modernity has come to prefer respecting that which is reasonable; rather in the world of argument it is that which comes from revelation or insight that is preferable and making sense of the evidence still obviously relies on there merely being evidence. In mathematics, what is proper is induction, called the forward implication that promises what is to be the truth of a matter based upon some axiom or set of axioms, whereas the converse relies on recurrence and fails among groups of ideas not freely generated (which is to say that when there is found something recurrent, there are only assumptions which point to the antecedent that caused it, and assumptions cannot lead to establishing anything axiomatic). What follows is an examination of a relation between that which we argue, and that which is unquestionable. It is my proposal that these two ends are convergent.

Convergence of Ideas

con·verge /kənˈvərj/ verb (of a series)

approximate in the sum of its terms toward a definite limit.

I believe intuition to be related to the mathematical idea of convergence, in that the ideas of people all attempt convergence towards the same idealized phenomena by the laws of human argument. I will begin by rehearsing the idea of convergence according to the laws of order in a topological number space, then I will relate these laws to those of order in human argument. (As an aside, I think perhaps the idea I am trying to represent needs to be furthered given the evidence that the current Wikipedia pages on the subject of convergence with respect to logic is a stub.) The idea of convergence, in consideration of numbers, is defined as follows:

A sequence \((s_n)\) is said to converge to the real number \(s\) provided that for every \(\varepsilon > 0\) there exists a natural number \(N\) such that for all \(n \in \mathbb{N}\), \(n \ge N\) implies that \(\left| s_n - s \right| < \varepsilon\).

Numbers

As a demonstration, imagine a sequence of numbers converging to the number \(1\) such that \(s = 1\). Let the beginning value of the sequence \(s_1\) be \(\frac{1}{2}\), and let the sequence be defined such that \(s_i = 1 - 2^{-i}\) for all \(i > 1\). This means that \(s_2 = \frac{3}{4}\), \(s_3 = \frac{7}{8}\), \(s_4 = \frac{15}{16}\), etc. From the listing of the elements it should be intuitive that the values of the sequence approach the number \(1\) while the set of numbers produced never actually includes the value \(s = 1\) — even though the sequence will always be converging closer and closer to the value \(s\).

For the matter of proving the convergence of the sequence, imagine a value \(\varepsilon = \frac{1}{8}\). In order that the definition holds given this particular \(\varepsilon\), there needs exist a natural number \(N\) such that the difference of each value of the sequence \(s_n\) to the value \(s\) is less than the value \(\varepsilon\) whenever \(n \ge N\).

Having the given \(\varepsilon = \frac{1}{8}\), it should be clear that whenever \(n \ge 4\), the difference between value of the sequence \(s_n\) and \(s\) is going to be less than \(\frac{1}{8}\) (this is because \(s_4 = \frac{15}{16}\), and each later \(s_n\) in the sequence is going to be greater that s_n by the definition of the sequence \(\left(s_n \right)\), so \(\left| s_n - s \right| < \varepsilon\)); therefore \(\left| s_n - s \right| < \varepsilon\) whenever \(n \ge 4\) (because \(\left| s_n - 1 \right| < \frac{1}{8}\) whenever \(n \ge 4\)). It still remains to be proven that the definition holds for any \(\varepsilon\), however the remainder of this proof is left as an exercise for the reader.

Arguments and Ideas

To restate my thesis, I propose again that this type of convergence has an analogue when it comes to making natural arguments. It is that (and I hope you will see the similarities between the definitions of convergence):

A sequence of statements, an argument, converges to the complete explanation of a phenomenon, when any ordinary person having intuition can understand the phenomenon being described, which happens only if the difference of understanding between the arguer and the listener is sufficiently negligible to allow both sides to be acquainted with the same phenomenon whenever the argument exceeds a certain length depending on the arguer and listener in question.

Consider an argument of a human sensation “I am sad because my dog died.” Most listeners to this statement will not need much further explanation, as most modern societies have long understood the companionship that people are capable of having with their domesticated animals. However if there is a society of people not having ever domesticated pets, then they may not understand completely this short explanation of the sensation. Nevertheless, in this case it suffices to merely give a longer argument, though it may take constructing a comparison between human-human or human-object relationships that the society is capable of understanding. This would be true under the assumption that this society has relationship assignments similar to our own (as is human), or upholds spiritual significance of ordinary objects (as is usually human). The furthered argument may be something like “I am sad because my dog died, which is similar to the feeling I would have if I lost my son or the precious, spiritually significant cross ordinarily worn around my neck.”

(Parenthetical remark: If at this point you are beginning to understand the point that I am making, then please take a look at my mathematics paper exploring this idea in relation to computational methods of generative grammars.)

mon·ad / ˈmōˌnad/ noun

a single unit; the number one.

I like to picture it as what is called the Monad (or perhaps The Absolute).

Any person can approach the point at the center of the image in the way that they are beginning to become acquainted with the argument, but only realistically stand on the circumference of the circle. I imagine the circumference to be human intuition, where the explanation of a phenomenon to another is merely synonymous with pointing towards the center of the monad which represents abstractly the phenomenon. (When a listener move closer to the position of the arguer, it is that they must be moving closer to the center of the monad, as their positions should also never be capable of existing in the same location.) Because human experience and argumentative explication consist only of a finite set of sensations, exact equality between understanding the phenomenon and being acquainted with it is impossible, and so the form of the monad will always be the circle with a dot at the middle of it. In another work of Bertrand Russell, he states:

"It often happens that we know that a certain phrase denotes unambiguously, although we have no acquaintance with what it denotes.... In perception we have acquaintance with objects of perception, and in thought we have acquaintance with objects of a more abstract logical character; but we do not necessarily have acquaintance with the objects denoted by phrases composed of words with whose meanings we are acquainted. To take a very important instance: There seems no reason to believe that we are ever acquainted with other people's minds, seeing that these are not directly perceived; hence what we know about them is obtained through denoting. All thinking has to start from acquaintance; but it succeeds in thinking _about_ many things with which we have no acquaintance."

I will not say anything on the subject of denotation. (I do not want to embark on such a lengthy subject having already employed the definition of a convergent sequence. My argument could perhaps be continued in arguing something like Bayesian thinking, but again I am wanting to stop.) So, I will end the blog post with a quote by Paul Erdős, another mathematician. To me, denotation is beauty, and being able to make comparison between something and another thing that is unambiguous like numbers is beautiful.

"Why are numbers beautiful? It's like asking why is Beethoven's Ninth Symphony beautiful. If you don't see why, someone can't tell you. I know numbers are beautiful. If they aren't beautiful, nothing is."